I arrived at the airport in Tripoli, Libya, on assignment for CBS Radio with my paperwork in order. I even had the phone numbers of local immigration officials in case anything went wrong.

It quickly did.

An airport official said my papers wouldn’t allow me into the country, even though the visit had been approved by the Libyan Embassy in Washington, D.C.

He put me on the next plane leaving Tripoli, and I ended up in Vienna, Austria. Turns out that the militia controlling the airport had a beef with the Washington Embassy and wasn’t recognizing its authority to issue visas.

It was 2012, not long after the US and other Western powers had overthrown Muammar Gaddafi and brought “democracy” to the country. But Libya was already on its way to becoming a failed state ruled by competing warlords, as my airport experience affirmed.

In 2011, President Barack Obama and his liberal interventionists justifiedyet another disastrous invasion by claiming they were protecting civilians from a murderous dictator. But very soon, the actions of Washington and its allies created chaos.

“Libya is a failed state,” Barah Mikail, associate professor at Saint Louis University in Madrid, tells me in a phone interview. “It is a country with spheres of influence, not a government.”

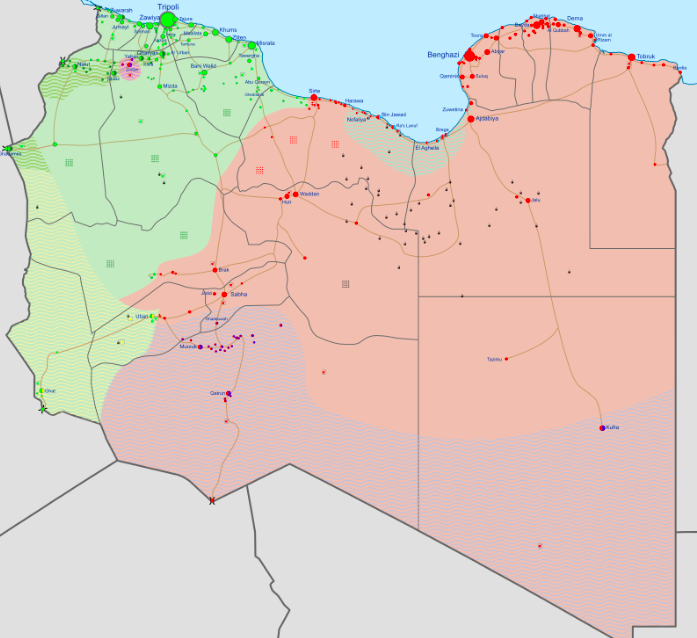

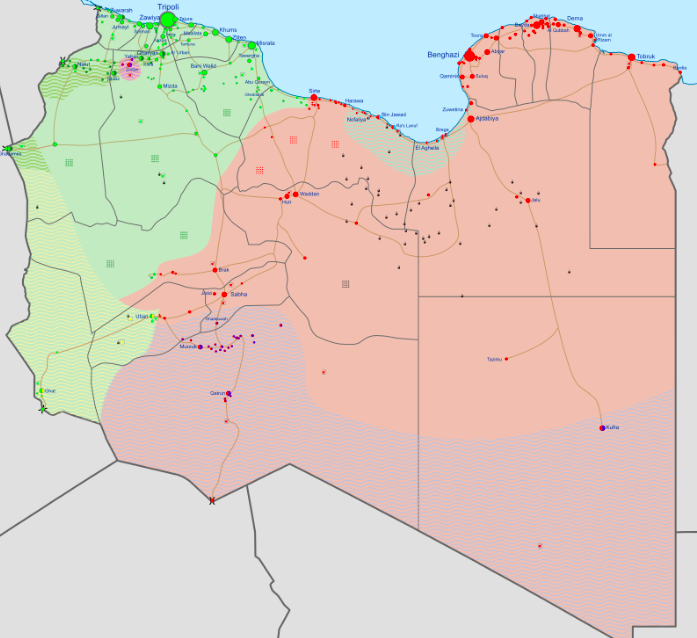

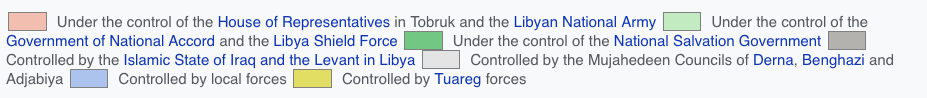

Today, a myriad of outside powers compete for dominance in Libya, none of which care much about the country’s people.

Turkey, Qatar, and the Arab League back the so-called internationally recognized government, which is actually an alliance of political Islamist and extremist groups in Tripoli. Russia, France, Egypt, and the United Arab Emirates support military dictator Khalifa Haftar based in Benghazi.

The Trump Administration has no coherent policy towards Libya, which has given a free hand to the other intervening powers.

“It was a mess from the beginning,” Vijay Prashad, author of the 2016 book The Death of the Nation and the Future of the Arab Revolution, tells me. “This was not an uprising against Gaddafi. It was a regional war.”

Imperialist interests

Because of its rich reserves of oil and natural gas, outside powers have long sought to dominate Libya, a country of only 6.9 million people. More recently, with the collapse of the central government, terrorist groups have sprouted up, contributing to regional instability. Immigrant smugglers also use Libya as a jumping off point to Europe.

Libya was once in the anti-imperialist camp. In the early 1970s, Muammar Gaddafi, who had come to power in a military coup, allied with rising anti-imperialist movements to oppose US policy. But over time, he became just another corrupt dictator soliciting bribes from foreign powers.

By 2003, Gaddafi made a 180-degree turn and allied with Washington, giving up his nascent nuclear weapons program and opening his economy to additional exploitation by Western corporations.

“He was our partner,” Mark N. Katz, professor of Government and Politics at George Mason University, tells me by phone.

But Gaddafi was an expendable partner. In 2011, when Arab Spring protesters ousted dictatorial regimes in Tunisia and Egypt, Libyans took to the streets as well. Western powers saw an opportunity to replace Gaddafi with an even more pliant ruler.

In March 2011, French, British, and US air forces bombed Libya, causing huge damage to the country’s infrastructure. Western powers supported efforts to write a new constitution and hold parliamentary elections. But real power stayed with local militias. The country began to fall apart.

“Other countries parachuted in Libyans who had been living in Arab countries and the US,” says Prashad. “The militias didn’t see them as leaders.”

Nevertheless, the Obama Administration saw Libya as a great success story for its policy of humanitarian intervention, with Secretary of State Hillary Clinton proclaiming, “We set into motion a policy that was on the right side of history, on the right side of our values, on the right side of our strategic interests in the region.”

History has judged the invasion far more harshly.

“How can you talk about the right side of history when you’ve just destroyed a country?” asks Prashad.

Recent fighting

General Khalifa Haftar, the leader of the powerful Libyan National Army, launched a major offensive against Tripoli in April 2019, promising quick victory. He relied on the backing of Russian mercenaries and arms from the United Arab Emirates. The former CIA asset claims to represent secular forces but allows extremists to control the mosques in areas under his control.

Haftar’s military offensive ran into fierce opposition in January of this year, when Turkey sent troops and sophisticated arms to back the Tripoli-based Government of National Accord. For years, the GNA controlled little more than that capital city. It consists of various political Islamist parties and militias, including the Muslim Brotherhood and the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group, formerly affiliated with Al Qaeda.

The GNA also relies on extremist Syrians and Libyans who returned home after fighting Bashar al Assad’s government in Syria. These brigades, politically close to Al Qaeda, were the most experienced fighters, according to Wolfgang Pusztai, Austria’s former defense attaché to Libya.

“These guys are crazy,” Pusztai tells me in a phone interview from Vienna. “But they were the backbone of the anti-Haftar fight in the first months.”

The Pentagon supports the GNA in Tripoli and offers low-key military cooperation. But Washington has generally pulled back from Libya and allows Turkey to do the heavy lifting.

The nearly decade-long war and outside intervention has been disastrous for Libyans. According to the United Nations, 1.3 million Libyans need humanitarian assistance and 200,000 are internally displaced. Human Rights Watch notes that all sides are guilty of violating the laws of war and, in some cases, of committing crimes against humanity.

Peace prospects?

Since June, the GNA and Turkey have been on a military offensive towards Benghazi, Haftar’s stronghold in eastern Libya. Egypt, a Haftar ally, has threatened to intervene militarily.

Egypt and Haftar have called for a ceasefire and peace talks, reflecting Haftar’s weakened military position. So far Turkey and the GNA have rebuffed this peace effort.

In the past, Washington would have maintained occupation troops in Libya, or at least sent a lot of arms to a political faction. But both the Obama and Trump Administrations have backed away from Libya, a sign of a weakened empire.

Eventually there will need to be a political settlement in Libya, but not until the major players recognize they can’t win militarily.

“Foreign interference and delivery of weapons is the main problem,” analyst Mikail says. “If this stops, we’ll have a different landscape.”

Reese Erlich’s nationally distributed column, Foreign Correspondent, appears every two weeks. Follow him on Twitter, @ReeseErlich; friend him on Facebook; and visit his webpage.